Will 2026 see the Geopatriation of the Cloud?

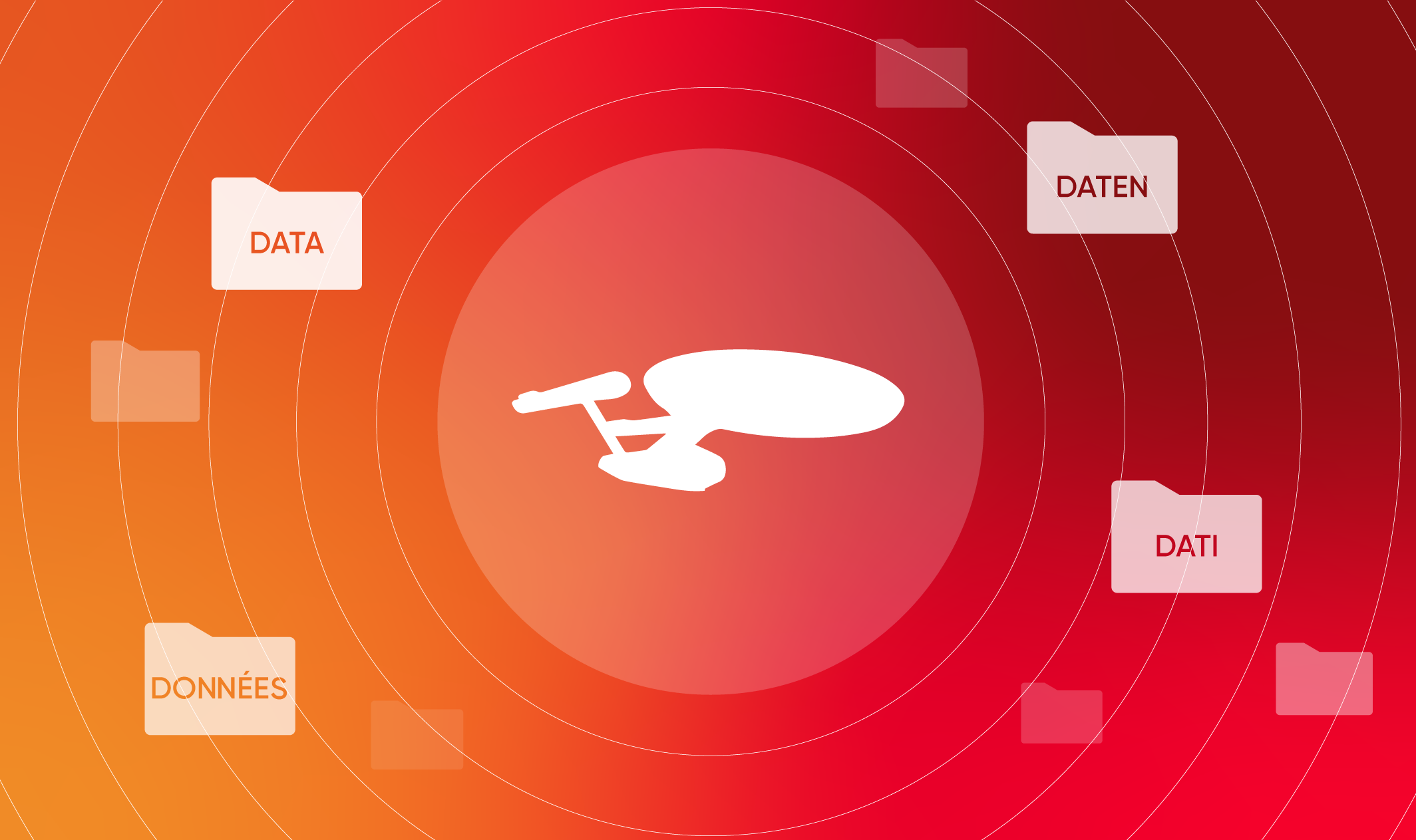

“Captain’s log, stardate 2026.1. Citizens of Europe are increasingly concerned about their reliance on the US cloud platform industry. Will we see a significant geopatriation of such services in the coming year?”

While a made-up Star Trek quote may seem an odd link to the current geopolitical situation between the EU and the U.S. when it comes to Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and digital sovereignty, it is actually quite pertinent. Core to the Federation’s ideals were two points relevant to today’s discussions:

- Just because we can intervene doesn’t mean we should.

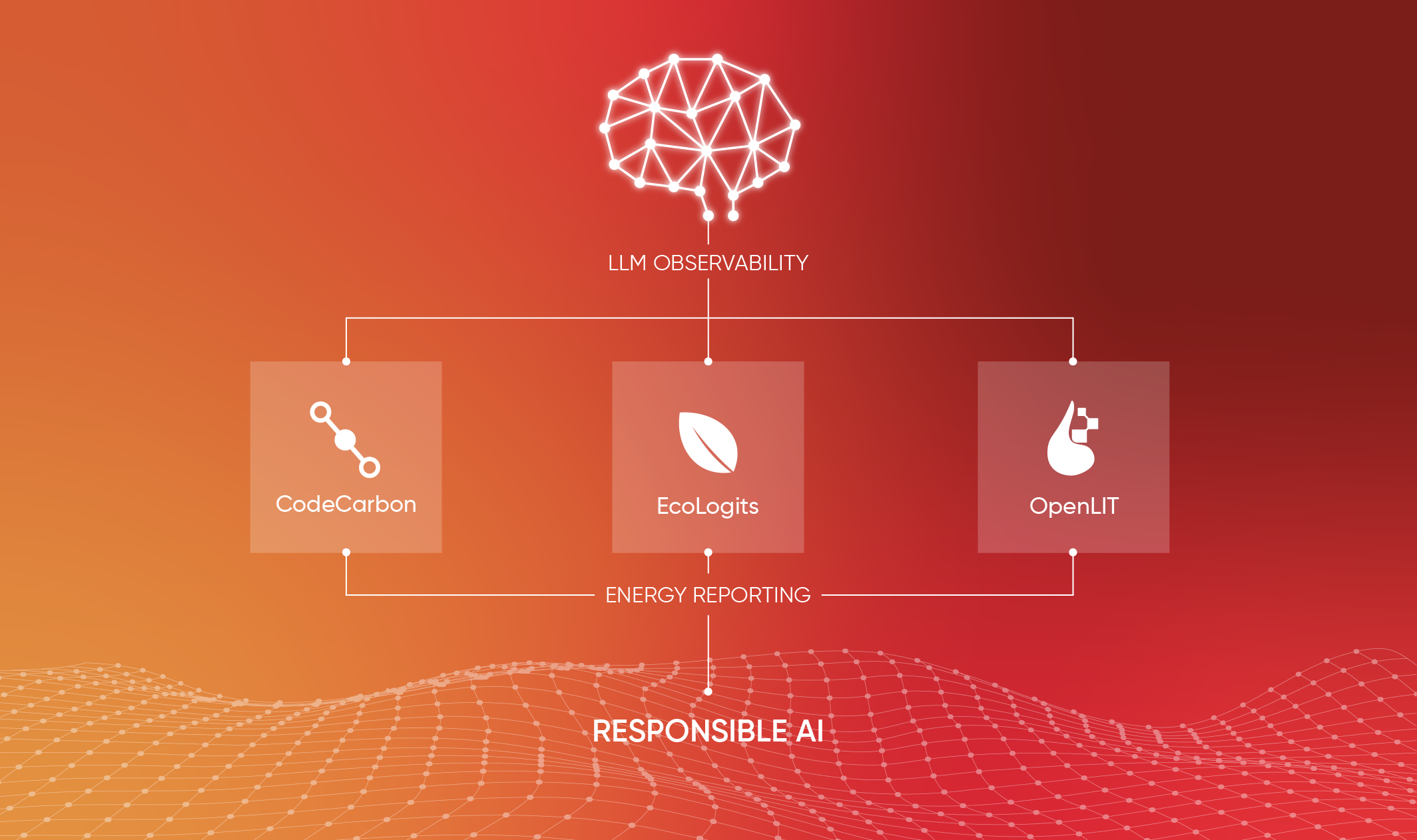

- Technology has to be more than impressive; it needs to be safe, ethical, and accountable.

Regarding the first ideal, the U.S. CLOUD Act[1] allows their law enforcement agencies to access data stored by U.S. IaaS providers, even if that data is located in Europe. And with respect to our second ideal, we can highlight the current bruhaha surrounding Grok. Yes, generative AI can create sexualised images from photos, but who on earth decided that this capability should be made available to anyone, let alone everyone?

As a result, many Europeans are asking themselves: Is this what we want?

So how did we get here?

Let’s roll back briefly to 2019, when Donald Trump was president of the U.S. and Germany’s Chancellor was Angela Merkel. At an employer’s conference in Berlin that year, she stated [2]:

“So many companies have just outsourced all their data to U.S. companies. I am not saying that is bad in and of itself – I just mean that the value-added products that come out of that, with the help of artificial intelligence, will create dependencies that I am not sure are a good thing.”

Jumping forward to 2025 and reflecting on the erratic nature of Donald Trump’s trade and geopolitical strategy, his government’s penchant for complaining about European protectionism, and the tech bros fighting tooth and nail to avoid any level of accountability or regulation, it’s hard not to say “I told you so.”

So what happens next ?

Despite a GDP comparable to that of the EU, the U.S. has twice the global share of data center capability, and just three U.S. companies account for 65% of EU cloud services used [3]. So it’s hard not to start thinking that the answer should be that “cloud” will no longer mean global but, instead, mean local as European businesses geopatriate their data, AI services, and compute. However, in true European fashion, thus far there has been much talk and very little action.

But that’s changing. The resultant legislation is starting to take effect in 2026. One example is the Cloud and AI Development Act (CAIDA). Reflecting on the fact that the EU lags behind the U.S. and China when it comes to data center capacity, efforts will be made to triple capacity over the next 5 to 7 years [4].

Central to making this happen is resolving the bureaucratic hurdles that stand in the way. These range from the availability of land with the required natural resources (water, energy) and capital to invest, to the time needed to acquire permits. Technical advancements, such as the move to 800 VDC to power data centers [5], will ease some of these pressures as such infrastructure is constructed.

That this is being taken seriously is evident from the fact that it has become an Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI) [7], recognizing that this cannot be achieved by a single EU member country or individual companies.

The start of a digital decade

Of course, not everything required can be, or will be, sourced from Europe. For example, we’re still heavily dependent on Asia for chips and the U.S. for their design [8]. However, the stars are aligned around the importance of resolving the current imbalance. Beyond the cloud, we also have:

- Quantum Act: Support for the development of a quantum ecosystem that is essential for secure communication and tackling complex, high-dimensional problems in scientific research and AI.

- European Innovation Act: Developing innovation-friendly regulatory, policy, and investment frameworks to improve commercialisation efforts of digital and data-driven innovation.

- Chips Act “2.0”: Investment in R&D and semiconductor manufacturing, providing strategic and competitive autonomy and improved manufacturing capacity in Europe, building upon the initial legislation from 2023 [9].

More choice locally

It’s not that Europe doesn’t have any of these things. Nor is it the case that Europe seeks to build some sort of digital autarky, isolating itself from the rest of the tech world. It’s just clear that our reliance on others has become too great and that, like the Federation, differences in our ideals with some of our geopolitical partners are becoming too great to ignore.

Digital sovereignty and geopatriation are about ensuring local choice, especially when availability becomes limited or geopolitical tensions rise. Unfortunately, we’re talking about society’s digital infrastructure, and, much like a railway line or a road bridge, that means billions in investment. Hopefully, 2026 will see businesses not just storing data locally but thinking locally, as Europe instigates a permeable technological curtain that protects our business interests and values.

— — —

[1] https://www.apefactory.com/en/insights/digital-sovereignty-is-europe-prepared

[2] https://gpil.jura.uni-bonn.de/2020/11/germany-advocates-regaining-digital-sovereignty/

[3] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/779251/EPRS_BRI(2025)779251_EN.pdf

[4] https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/cloud-computing

[5] https://www.eu-cloud-ai-act.com/

[6] https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/building-the-800-vdc-ecosystem-for-efficient-scalable-ai-factories

[7] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6245

[8] https://www.european-chips-act.com/

[9] https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/european-chips-act

Never miss an update.

Subscribe for spam-free updates and articles.